This fall I took Anatomy of Style with Patrick Jones, an artist known for his fantasy oil paintings. At the start of the course he greeted us with an orientation video about our drawing materials: how to sharpen a charcoal pencil, how to prepare a charcoal stick for drawing, the best grip for these tools, etc. At the time I wondered, “Everyone seems to be working digitally these days. Is there a good reason for getting my hands dirty?” As it turns out, there’s a lot to be said for making a mess and forgoing the convenience of layers and Ctrl+Z.

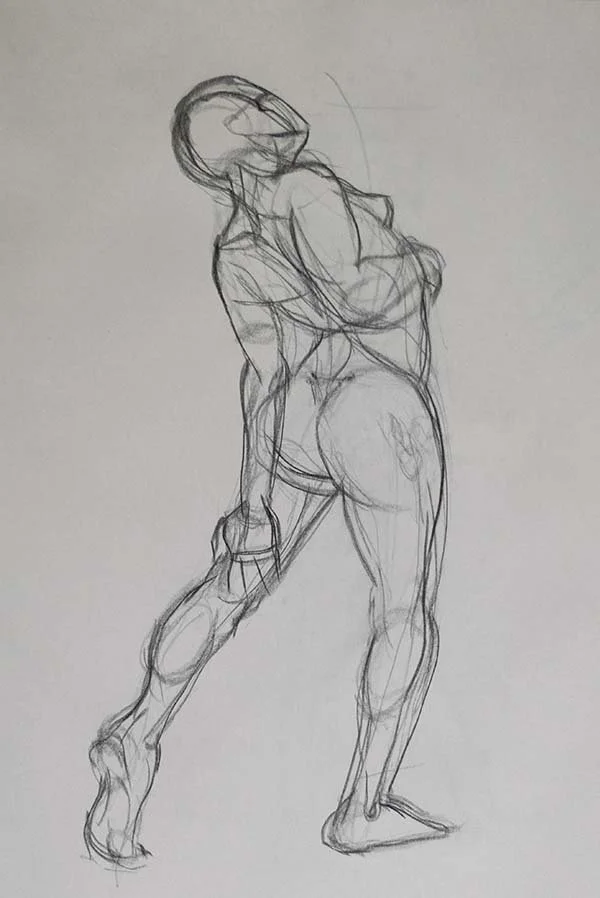

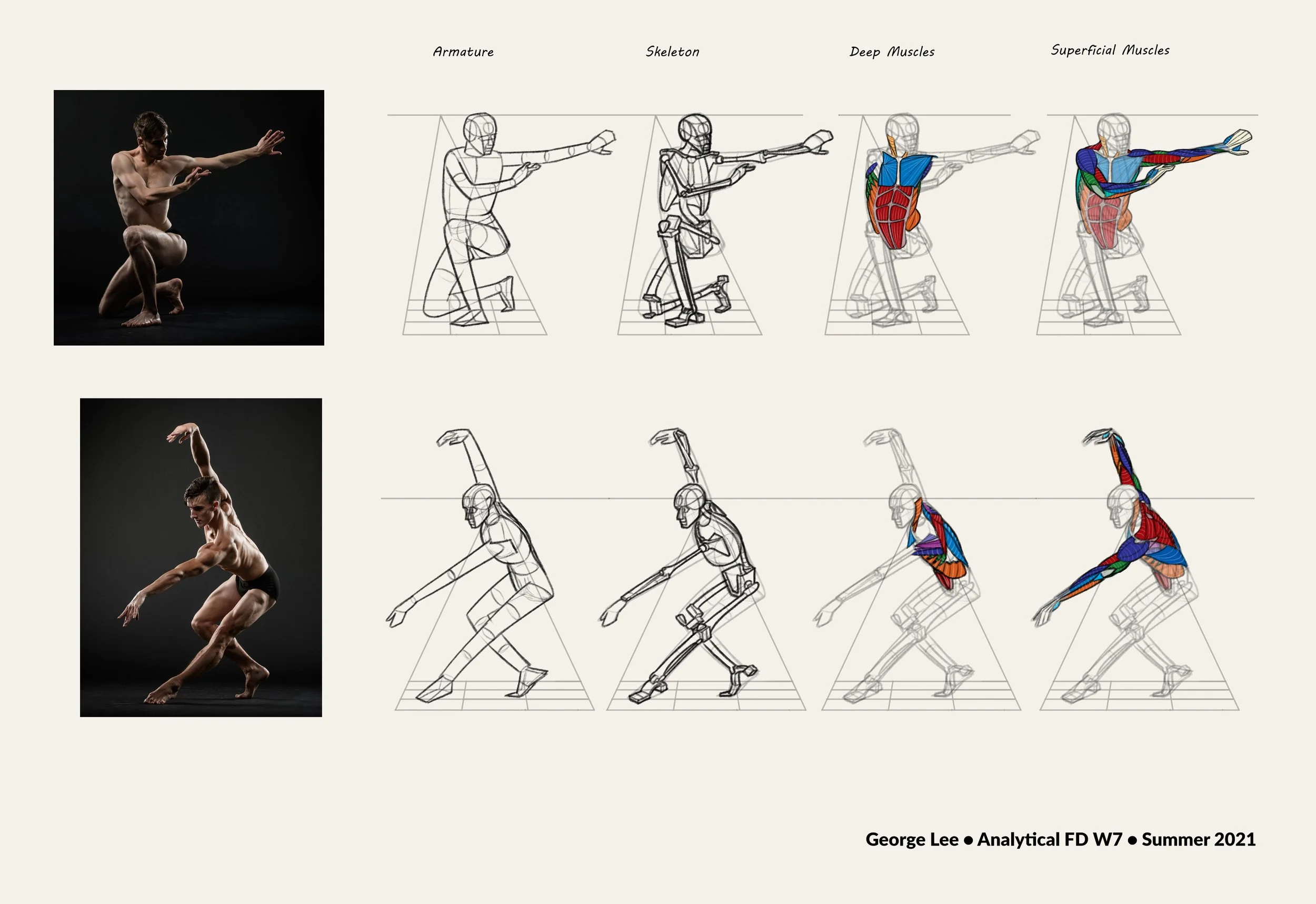

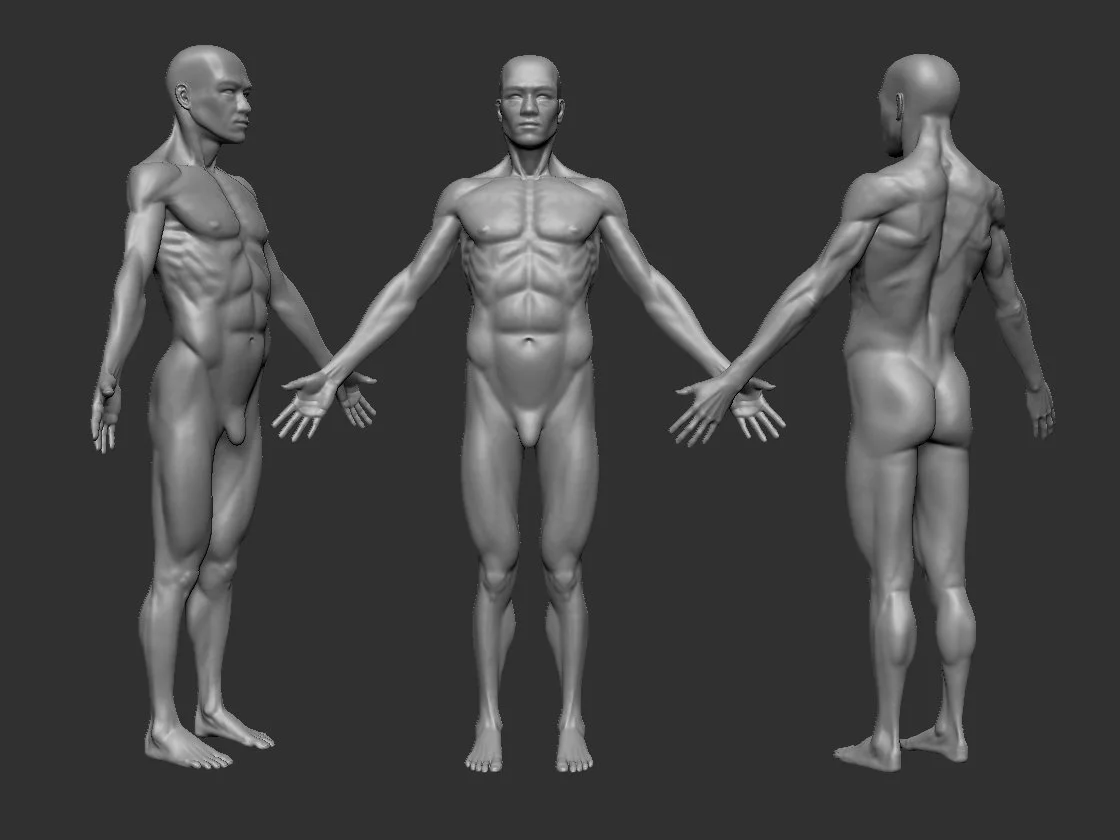

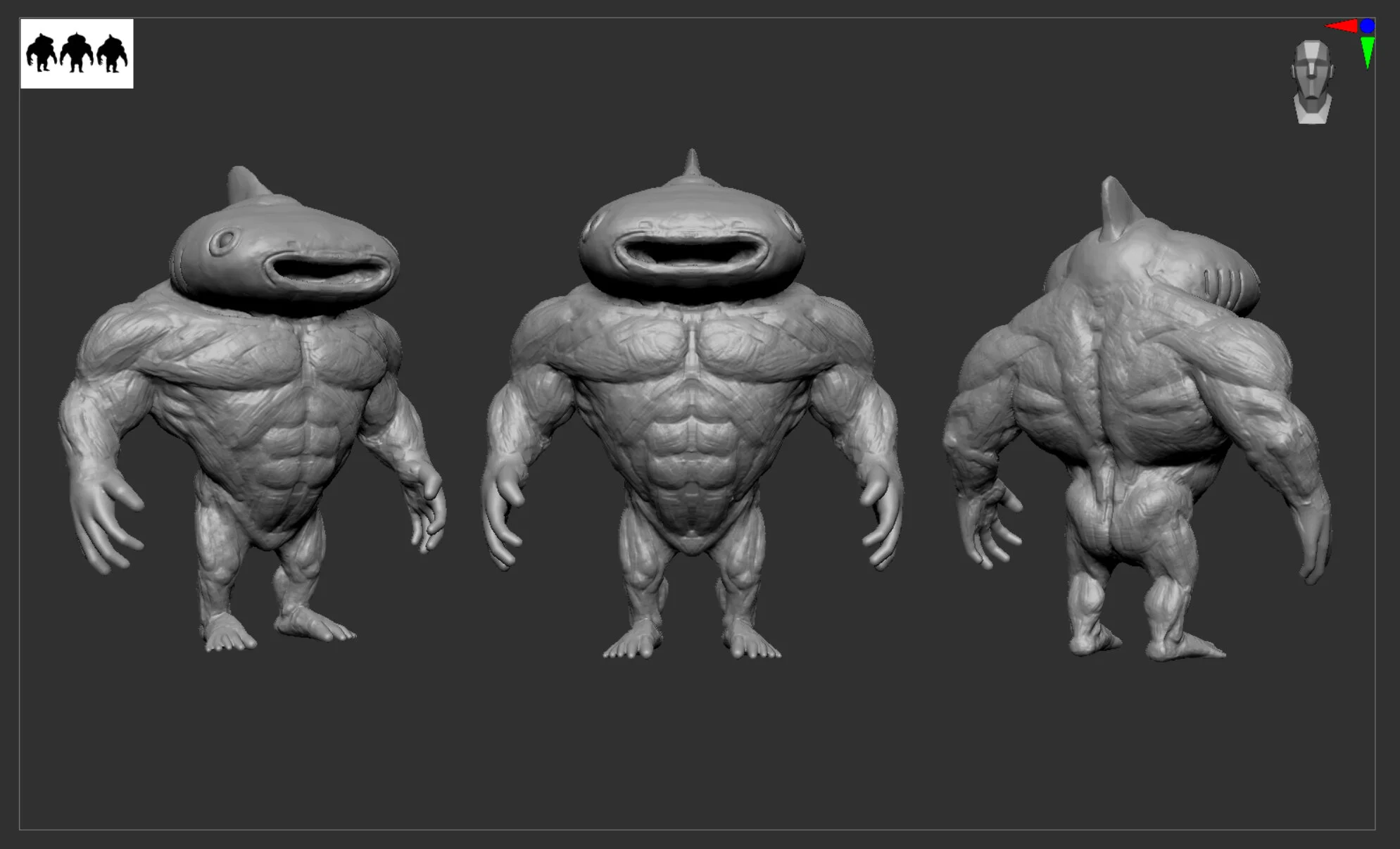

In contrast to the analytical approaches covered in previous semesters, Patrick’s approach to the human form prioritizes feeling and storytelling, finding rhythm and gesture, and using creative interpretation to develop your personal artistic voice.

Throughout his lectures, he emphasized that one of the biggest challenges for representational artists is to balance gesture and structure when depicting the human body. Too much focus on structure results in lifeless drawings (“structure hell”). Too much focus on gesture and you lose form and solidity (“gesture hell”). Rendering offers its own pitfalls: the artist that descends into “render hell” produces work that manages to look both laboured and lost.

One of the things I’ve noticed in my online art studies is the high attrition rate. Every class seems to have one or more lurkers that never submit work for feedback. I find this rather baffling because personalized feedback is the biggest benefit of enrolling in CGMA courses. The submission rate for final assignments seems to average around 50% (the most engaging teachers manage to get this up to 75%).

I’m sure the messiness of life plays its part: studies will take a back seat when work or family responsibilities arise. But I also wonder if there’s another reason. The Renaissance gave us great art heroes like Da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Artemisia. But those same heroes gave rise to the myth of artistic genius: the idea that you’ve either got it or you don’t. It’s a harmful idea that leads many aspiring artists to make unhealthy comparisons and to struggle with self-doubt. I see a lot of empathetic teachers playing coach and therapist to assuage their students’ doubts.

Getting back to dirty hands. One of the virtues of charcoal drawing is that a viewer can look at the restatements (pentimento) and feel the journey that the artist undertook. One of Patrick’s sayings that resonated for me is, “Every line is a thought.” It’s a simple but powerful idea that reminds me to be decisive when I put a mark down, but also to have the courage to accept my mistakes. To err is human, after all. Contrary to the myth of the artistic genius, art isn’t about perfection, a thing that springs from a genius’s mind fully formed. It’s fundamentally about connecting and relating to another human mind.